This article was written by Kartik Ghia, Systematic & Index Solutions Researcher at Bloomberg.

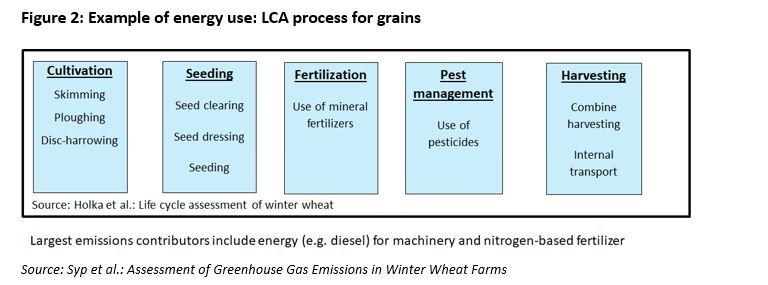

As sustainable themes have become increasingly integrated into the construction of equity and fixed income portfolios, investors have begun to extend their sights to the commodity markets. The key question is whether a systematic approach to sustainable investing can be adopted by commodity investors. In the first part of our blog series discussing sustainability in the commodity markets, we discuss investor rationale and objectives, a measurement framework of commodity-level GhG emissions, and implications for portfolio construction. (‘Can you extend sustainable investing to commodity indices?’, 4th October 2023.) Given most commodity investors hold derivatives-based portfolios, the emissions associated with each commodity is measured based on the production process, using a methodology called Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). The LCA model for each commodity maps the physical sub-processes from inception to the physical good referenced by the futures contract. This group of sub-processes is commonly referred to as ‘cradle-to-gate’. However, a natural question to ask is whether, in a similar manner to the production process, emissions from the consumption processes (i.e., the downstream use-cases) should be included. Since commodity investors are liquidity providers supporting hedging activity, portfolio construction can be interpreted as the reweighting of the portfolio to over-weight commodities with a lower per unit emissions to lower the associated emissions per US dollar exposure. In addition to the re-weighting on commodity futures, should investors consider the use of carbon credit futures?

Should consumption processes be included?

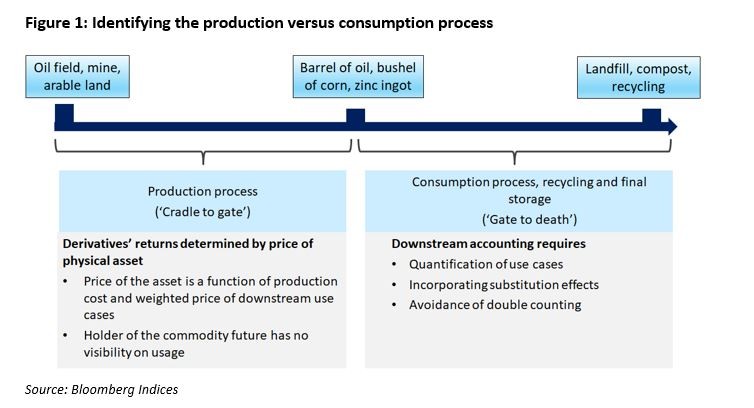

Commodity futures’ returns are determined by the price of the physical asset, which in turn is a function of the production cost and a weighted price of downstream use-cases. The physical and financial cost of producing a commodity is defined by what we refer to as ‘production processes’. The environmental physical costs can be viewed as externalities such as GhG emissions, wastewater produced and the impact on biodiversity. The downstream use-cases, typically a mix of intermediate and end-products, are made possible by physical processes that we refer to as ‘consumption processes’. Like production processes, consumption processes incur financial and physical costs. In LCA parlance, the production processes can be referred to as ‘cradle to gate’ while the consumption (and end-of-life storage) processes can be referred to as ‘gate to death’. In this article, we focus on why focusing on the ‘cradle to gate’ boundary is most appropriate in the case of derivatives’-based commodity investors.

In the previous blog, we discuss that financial investors do not directly affect demand and supply since they do not take delivery of the physical underlying commodity and therefore do not drive the use-case of the commodity. Commodities are among the primary building blocks for global industrial production and food supply, which means some commodities have a very wide range of uses. For example, crude oil can be used for transportation (combustion), electronics manufacture and in textiles to name a few. Additionally, modes of transportation post-production can significantly impact the level of per unit of production emissions. For example, a recent study discusses how maritime emissions differ during the transportation of crude oil depending on type of fuel used, vessel design and routing. Based on these considerations, the appropriate boundaries used for the life cycle assessment (LCA) calculation corresponds to the production process (‘cradle to gate’).

Inclusion of the consumption process has other difficulties, including the potential problems associated with double counting of emissions. Given the complexity of supply chains, and given the intermingling of intermediate and end-stage product emissions, estimating the average emissions value is potentially problematic. Furthermore, the confidence interval associated with this estimate is also likely to be large—and in many cases will result in the average estimates not being statistically different from each other. (The higher the level of statistical significance, the less likely the result is a result of chance). Furthermore, this also raises the question about whether to incorporate substitution effects and constructing reasonable forecasts. A good example is corn, which can also be used for biofuel production. In this case, should this be reflected as a credit for corn emissions and if so, how should it be incorporated?

A key concern for many investors is the incorporation of emissions from the downstream effects of energy-based commodities – primarily combustion. Estimates of emissions due to combustion can range from 70-100% of the emissions estimate for the production process. By restricting the estimation of emissions to the production process, are we reducing the relevance of our estimates for the six commodities in the energy sector?

To answer this question, we need to understand the role of energy-based commodities within the economy. Since crude oil, natural gas and the distillates are either a direct or indirect input for all sectors (including the energy sector itself), estimating the emissions due to the production processes already incorporates combustion-based emissions. Since the assessment is contained to the production process and covers the full commodity universe, the emissions from the uses of energy are captured by the analytic framework. Explicitly adding the downstream emissions from energy will lead to double counting of emissions.

What about carbon credits?

Over the past five years, the use of carbon credit futures to ‘net-out’ emissions from traditional derivatives-based commodity portfolios has become increasingly popular. The stated aim is to neutralize the emissions embedded within the production cycle of commodities. Part of the popularity of carbon credits has stemmed from the strong returns delivered by these futures for a variety of reasons including anticipated regulatory changes. However, there are three key reasons for circumspection.

First, carbon credits were intended for use by companies seeking to offset physical emissions; akin to the initial use-case for credit default swaps purchased by bond holders. The need to adhere to a ‘carbon budget’ might require the purchase of carbon offsets, which can be viewed as a tax on emissions. Since derivatives holders’ do not produce any physical emissions, it is difficult to see how this use-case is applicable to financial investors. In fact, in our previous blog on this topic (‘Can you extend sustainable investing to commodity indices?’), we discuss the need to construct an alternative interpretation for investors to measure the impact of their investment (‘funding support’) instead of the traditional equity and fixed income view of ‘portfolio emissions’.

Second, if investors intend to use carbon credits to compensate for the exposure to commodity futures, the carbon futures would need to be held to expiry—effectively writing-off the investment. This would be punitive from a portfolio return perspective and as expected. the most common implementations simply roll exposure to a deferred contract prior to expiry—effectively avoiding the offset. Indeed, even if investors did hold the carbon futures to maturity, the aggregation of GhG emissions across all commodities does not seek to over/underweight commodities by per unit emissions—instead treating the basket as a single entity. This implies a different objective from a traditional tilted portfolio.

Lastly, for a given commodity, the ‘price’ of a unit of GhG emissions differs by region. The price dynamics of carbon credits vary by region since it is a framework that is effectively geographically localised by regulation; governed by governmental policy which dictates the supply and demand for credits and local company efficiencies. Accordingly, if an investor should choose to offset the assigned emissions within the commodity portfolio, what is the carbon credit basket comprised of? This raises further computational, liquidity and operations questions such as: does the mix of carbon credits need to be matched to the geographical production profile of each commodity and what are the contracts available for offsetting? Given the complications raised above, incorporating carbon credits within the carbon titled framework can be viewed as premature; with reasons ranging from traditionally intended use-cases to implementation.

What are investors’ implications?

Financial exposure to commodity markets has traditionally been gained through the futures markets. Investors seeking to gain exposure to the economic cycle, hedging inflation and diversifying equity and fixed income returns, roll futures positions prior to expiry. The purely financial exposure without receiving physical delivery results in investors (1) having a role as liquidity providers with no direct link to the demand and supply of the commodity and, (2) no ability to specify the downstream use-case including geographical location. Given the role of investors, consistency in measurement would require the calculated emissions for each commodity be restricted to the production processes. The aim of carbon credits along with the geographical specificity of carbon pricing make it challenging to incorporate within a framework whereby the goal is to reweight commodities within a traditional benchmark in-line with the principles of sustainable development.

The Bloomberg Carbon Tilted Commodity benchmark (Bloomberg Terminal ticker is BCOMCA Index) is an index that reweights the Bloomberg Commodity benchmark (BCOM) based on the calculated emissions from the production processes of each commodity. The reweighting process is restricted to the individual sectors to reflect the weak substitutability requirement for commodities that are over/underweighted.

The data and other information included in this publication is for illustrative purposes only, available “as is”, non-binding and constitutes the provision of factual information, rather than financial product advice. BLOOMBERG and BLOOMBERG INDICES (the “Indices”) are trademarks or service marks of Bloomberg Finance L.P. (“BFLP”). BFLP and its affiliates, including BISL, the administrator of the Indices, or their licensors own all proprietary rights in the Indices. Bloomberg L.P. (“BLP”) or one of its subsidiaries provides BFLP, BISL and its subsidiaries with global marketing and operational support and service.