ARTICLE

Saudi Arabia, MBS are far from ending their reliance on oil

Bloomberg News

This article was written by Abeer Abu Omar and Christine Burke at Bloomberg News. It appeared first on the Bloomberg Terminal.

Around a decade ago, Saudi Arabia’s now Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) said the kingdom’s economy would be able to survive without oil by 2020, a claim he linked to huge investments aimed at steering the country into a new era. Today, key indicators show the government remains just as reliant on petrodollars, if not more so.

The push to end Saudi Arabia’s “addiction” to crude oil, as MBS himself put it a short time later, has led to major social and economic changes. Millions more women have formal jobs, tourism has surged and new industries from electric vehicles to semiconductors are growing.

Yet economic diversification, a central aim of MBS’s Vision 2030 plan, is happening more slowly than the government hoped. Saudi Arabia’s dependence on oil revenue is largely unchanged from 2016 and has even deepened by some measures.

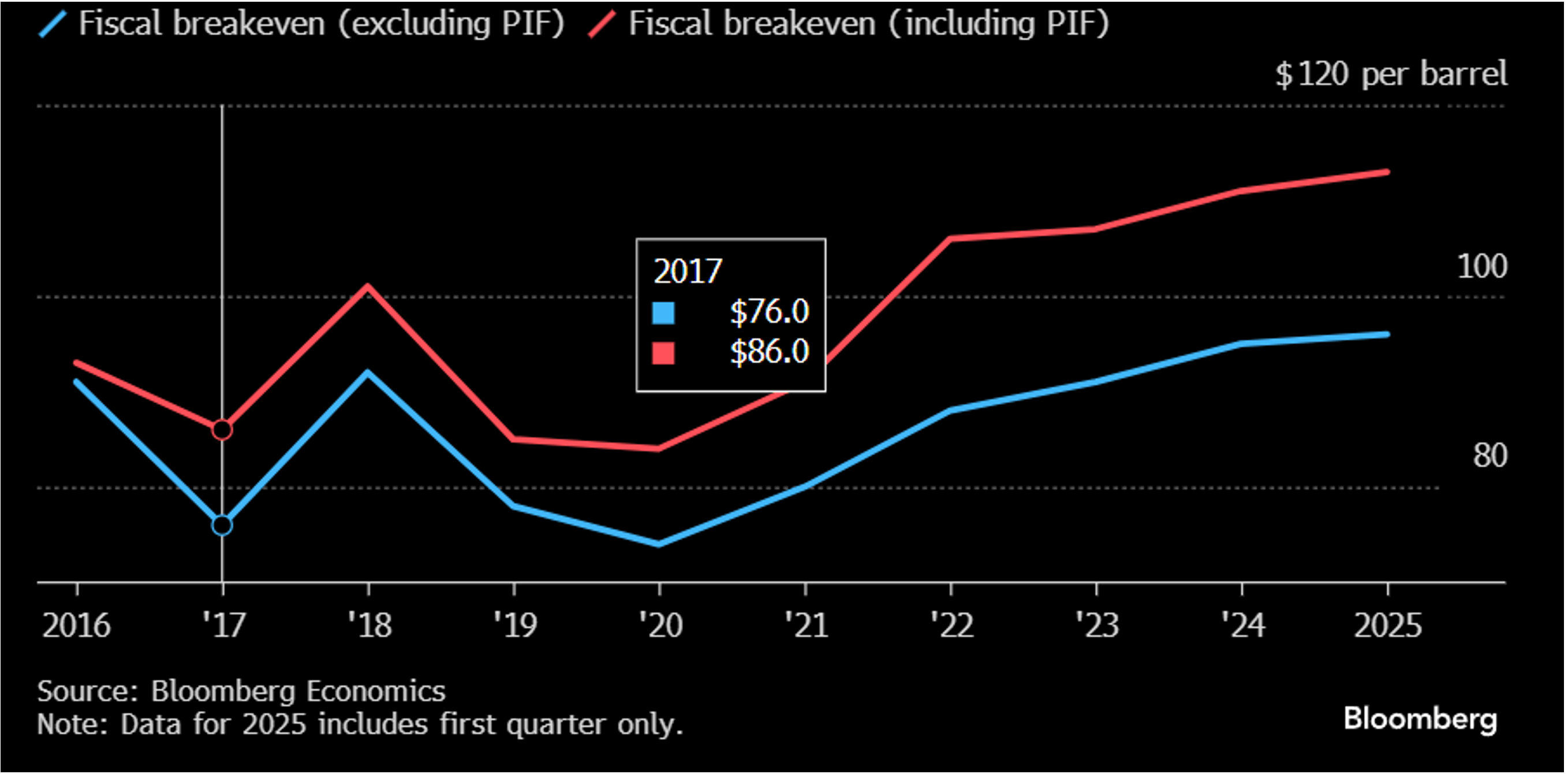

Saudi Arabia needs higher oil prices than in 2016

PIF domestic spending takes the fiscal breakeven price to over $100

The Gulf nation’s fiscal breakeven oil price now stands at $96 a barrel, Bloomberg Economics estimates. That’s higher than a decade ago and if domestic investment by the sovereign wealth fund — crucial to Vision 2030 — is included, the figure is $113.

While that is seen as a rudimentary measure by some economists, it gives a guide as to what oil price the kingdom’s budget can handle. Since the beginning of 2024, Brent has averaged just $76.50, leading the government to ramp up borrowing in international bond markets and consider more asset sales to help finance its fiscal deficit.

“The core aim of Vision 2030 is to cut oil dependence,” said Ziad Daoud, Bloomberg Economics’ chief emerging markets economist. Yet “the kingdom has become more reliant on oil.”

In addition to the budget breakeven, Daoud said Saudi Arabia needs a higher crude price than in 2016 to balance its current account, or pay for imports and offset outward remittances. “This is mainly because of surging public spending,” he said, “not just on glitzy mega-projects but also due to implicit popular pressure to ramp up outlays when oil rises.”

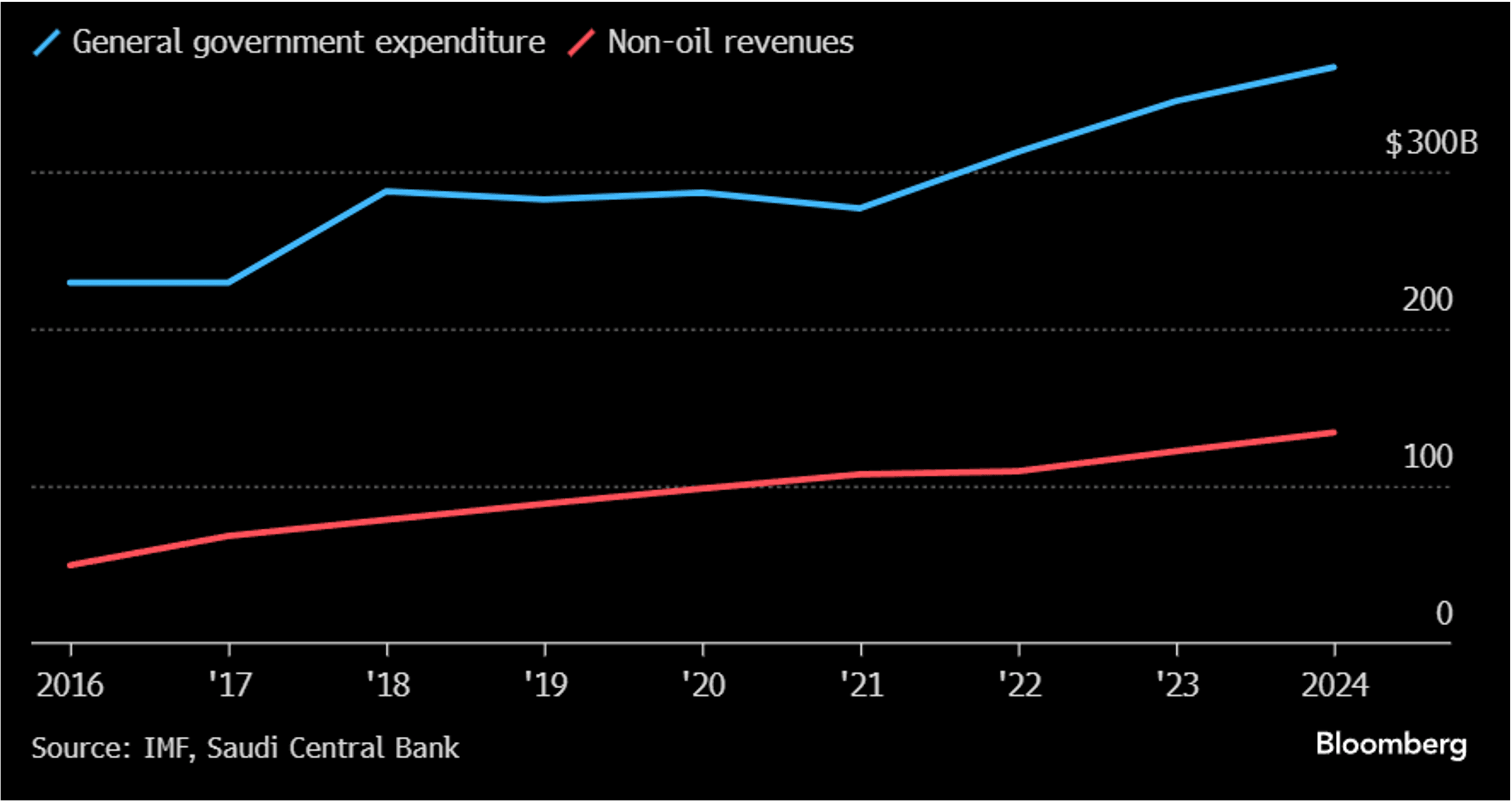

Rising non-oil revenues far offset by increase spending

Saudi Arabia tends to raise expenditure at times of elevated oil process

The government has historically hiked spending when crude prices are elevated, an approach it planned to forgo as part of the push to reduce its reliance on oil. Finance Minister Mohammed Al-Jadaan has said officials don’t “even look at the oil price” any longer.

Still, oil continues to provide about 60% of government revenue and accounts for more than 65% of exports.

Finance officials outlined plans to trim spending in 2025 after overshooting targets the previous year. That was partly because of expenditure on the so-called giga projects, which include the new city of Neom and a cube-shaped skyscraper in Riyadh big enough to fit 20 Empire State Buildings. It was also due to accelerated investments to boost new industries.

“Saudi Arabia continues to advance the Vision 2030 agenda with determination, despite global economic headwinds and regional volatility,” a finance ministry spokesperson said in a statement to Bloomberg. “The structural transformation of the Saudi economy is not a short-term project. It is a generational endeavor that is already delivering measurable progress across key sectors. Saudi Arabia’s fiscal position remains robust.”

The non-oil economy grew more than 4.5% in the first quarter of this year, consistent with government targets. The sector now makes up more than half the country’s $1.1 trillion of gross domestic product.

Revenues from the non-oil sector have risen substantially, to over $134 billion in 2024 from about $50 billion in 2016. Yet higher government expenditures have offset much of those gains, resulting in the kingdom running fiscal deficits every quarter for more than two years.

“Given the sharp increase in government spending over the last few years and the fall in the oil price this year, a more cautious fiscal stance is prudent,” said Monica Malik, chief economist at Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank PJSC. “Saudi Arabia has strong fiscal buffers, though these could be eroded quickly.”